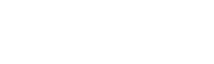

Encore: Man Ray and the Violon d’Ingres

Or: the enchantment of a beautiful back.

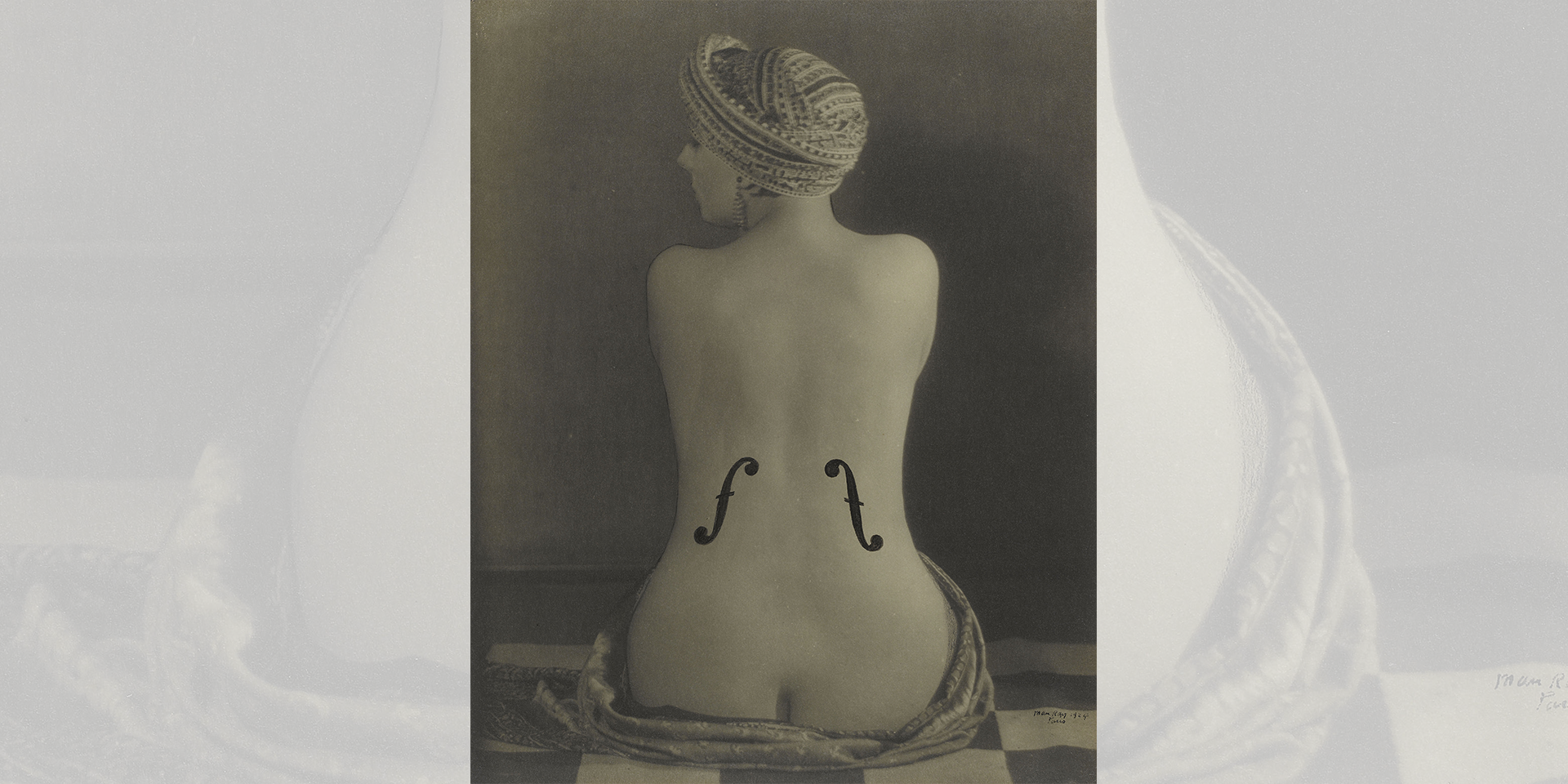

Let's take a – perhaps the – icon of surrealism: Man Ray's Violon d’Ingres. A photograph of the ravishing back of a woman, shaped like the body of a violoncello with two f-holes, which bears the title: Violon d’Ingres. The voluptuous back – 'un cumulo di curve' in the words of Fred Buscaglione – is more reminiscent of a cello than the much smaller and more delicate violin. The body of the woman and the body of sound, form and instrument creating an ambiguous figure: the cello appears first, then the back in the foreground. Ingres was a painter known for the most beautiful backs of the world, those of his odalisques. And such an Ingres, the back view of an odalisque, is evoked in the photograph both by the pose of the woman, but also by the turban, a play between painting and photography. Violon d’Ingres is also telling in the sense that Ingres could not only paint, but also play the violin. An activity that is not carried out professionally, but instead enthusiastically as an amateur, has since become known as a Violon d’Ingres, a dada, a hobby horse. One gently strokes the string instrument being played to elicit sobbing, exulting, wildly vibrating tones. The onlooker dreams of playing on this woman's back as an amateur players the violin, coaxing from her as a body of sound the most wonderful sounds of lovemaking. Libertine wit is this game between title and picture, a game of love. Jeanloup Sieff quotes and adapts Man Ray's joke in his photograph of a dress from Yves Saint Laurent's winter collection 70/71. The photograph immediately recalls Man Ray's Violon d'Ingres: the back in contrasting black and white, the turban, head position and image detail are the same. Like Man Ray, this back view of Kiki de Montparnasse's back shows the tantalising décolleté of the buttocks. Here it is not the collage-like treble clef that opens up the body from the inside into the body of sound, but the floral lace. On the one hand, it emphasises the violin-like shape of the back, lightly covering the skin with the refined black flowers of evil and opening it from the inside into a body of sound in an interplay of lace and flesh. The orientalism of the odalisque, the epitome of the erotically attractive woman, created for the pleasures of eros, is alluded to in this arabesque ornamental lace. One recalls Proust, for whom Venice was disguised behind its Moorish stone peaks as a mysterious harem, the promise of a city of a thousand and one nights.

Mrs Barbara Vinken, Professor for French and Comparative Literature at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich (Germany)