Man Ray and Simon Baker

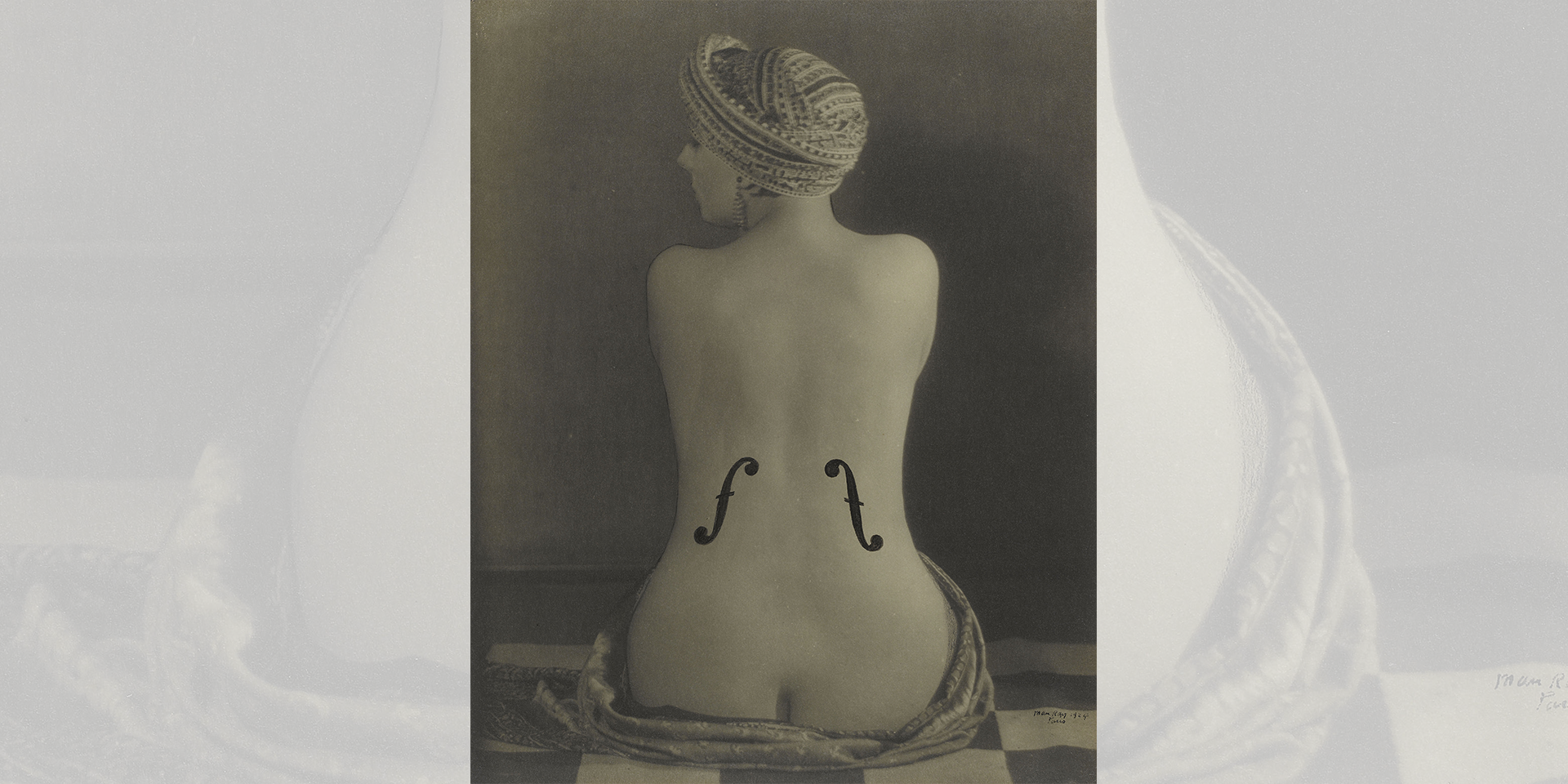

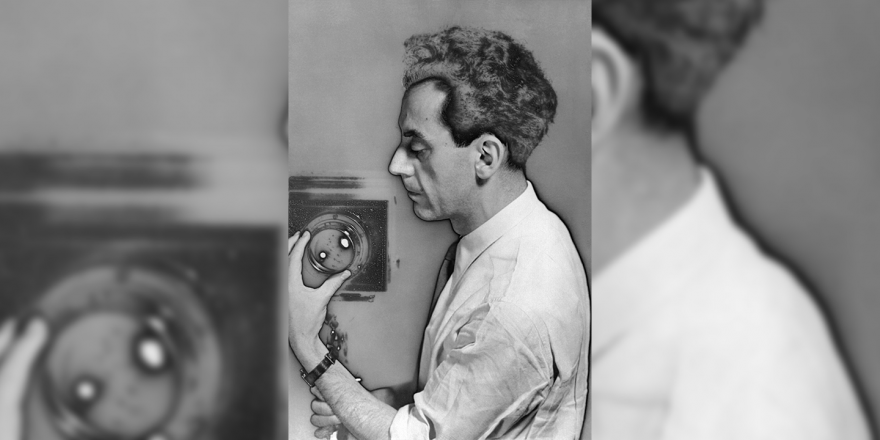

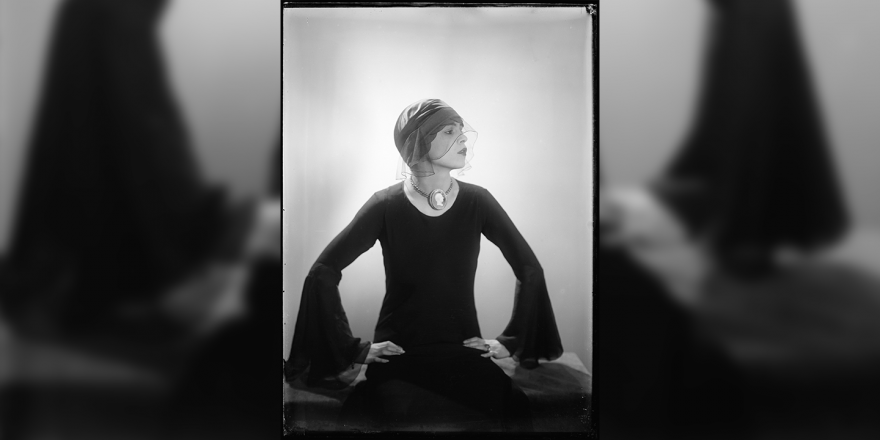

At this time of confinement, isolation and social distancing, it seems particularly important and appropriate to think again about Man Ray, an artist who not only travelled freely ‘in person’ (moving with ease from the United States to France and back over his long career) but who published extensively in avant-garde magazine that took his work around the world without him. In a way analogous with the way that, today, we share images online across vast distances, Man Ray’s work circulated widely: from early small-scale publications such as the Ridgfield Gazook in the USA; to his interventions in Dada publications like 391 and Litterature; and then his participation in more successful surrealist titles like La Revolution Surrealiste and Minotaure. In his both his ‘avant-garde’ and ‘commercial’ activities, which are interwoven and interrelated, Man Ray was as often, or more often, present on paper, as on gallery walls. As a ‘lens-based artist’ (to use a useful anachronism), working between formats and modes of delivery, (demonstrating again and again the notion of photography as a medium grounded in its ‘technical reproducibility’), Man Ray remained, above all, committed to interdisciplinary practice: to the total freedom to move between the media he used to express himself. In another pertinent analogy with today’s generation of artists using cameras, who are likewise unlikely to want to be pigeonholed into being ‘photographers’ or ‘painters’ etc., Man Ray had a healthy ambivalence about such categories. Using elements of photography, be it cameras (still or moving), or the darkroom (with or without cameras), he nevertheless considered himself what we now call ‘a contemporary artist’, comfortable and confident making paintings, sculptures, films and, photographs, and often using more than one of these media for a single work. At different points in his professional life he presented himself differently. In 1934 when he published Man Ray 1920-34, he seems to be a master photographer and advocate for the status of the medium; by 1966, for his retrospective at LACMA he seems almost completely to have excised photography from his back catalogue (photographs often surviving only as the supports for assemblages and objects). This nimble, productive ambivalence about the medium with for he is nevertheless best-known today is crystallised in his 1924 work Le Violon d’Ingres. Almost ‘just’ a photograph (with the subtle montaged f-holes on the back of his model Kiki de Montparnasse), it is more likely a complex Dada game played out between work and image; like the multiply captioned photograph Dust Breeding that he had made for, and with, Marcel Duchamp and Andre Breton; or the many images he submitted for surrealist captions and textual contamination in magazines and books. Like the best of these, Le Violon d’Ingres works between image and text and allows for misinterpretation and misreading. The original French phrase refers to the legendary ability of the painter J.A.D. Ingres to play the violin well: it means being good at something that is not your principle metier or vocation. Looking at this work, the ‘second skill’ could be many things. It could be photography for Man Ray - after he began his career as a painter and continued to paint. It could equally be dada or surrealism (for either Man Ray himself or the original image) - in reference to the addition of the montage elements to the surface of an otherwise ‘straight’ photography. It could be the second ‘skill’ of his subject Kiki, who is in the process of ‘becoming’ a violin through the objectification of the shape of her body. But the title can also be read literally, in English, as referring to Violent Anger: after all, both Man Ray and Duchamp loved the effects that arose from playful mistakes and slips in translation between French and English. In which case, the title might refer to the careful violence metered out to the surface of the representation of a woman. For an artist who refused to choose whether he was one thing or another, painter or photographer, surrealist or commercial photographer, it is however most likely that in giving the work this title, Man Ray preferred not to limit himself to a choice of possible options, but instead to keep them all open at once.

Simon Baker, Director, MEP, Paris

Associated content

Man Ray and me

Man Ray and Fashion

General guided tour